by Fred Brouns - Health Food Innovation, Human Biology, Maastricht University, The Netherlands; Luud Gilissen - Plant Research International, Wageningen University & Research Centre, The Netherlands and Department of Plant Biology and Crop Science; Peter Shewry - Rothamsted Research Centre, United Kingdom; Flip van Straaten - Dutch Bakery Center, Wageningen, The Netherlands

Published in Milling and Grain, March 2015

In November 2014 a proposal to initiate an evidence-based evaluation of the effects of wheat types and food processing in the context of wheat and gluten avoidance was presented to the European Health Grain Forum. This proposal addresses a global issue and has significant pre-competitive importance for all grain/cereal food chains.

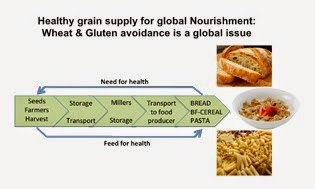

Worldwide an anti-gluten and anti-wheat hype has developed over the past four years, with significant impact on all parts of cereal supply chains. This has resulted in significantly reduced sales of bread, breakfast cereals and pasta products in various markets impacting also on the supply chain (see Figure 1).

Of all grains, wheat is most widely cultivated worldwide.

Wheat is third among all cereals, behind maize and rice, in total global production, which is over 700 million tonnes annually. The demand for wheat for human consumption is also increasing globally, including in countries, which are climatically unsuited for wheat production, due to the adoption of western-style diets.

Wheat is relatively rich in micronutrients, including minerals and B vitamins, and supplies up to 20 percent of the energy intake of the global population (1).

Nevertheless, an ever-increasing demand for gluten-free and wheat-free products has developed in recent years.

|

| Fig 1: The wholecereal supply chain carries responsibility in terms of feeding |

About 95 percent of the wheat that is grown and consumed globally is modern bread wheat (Triticum aestivum), a relatively new species, having arisen in southeast Turkey about 10,000 years ago (2).

Cereal (including wheat) proteins that may cause allergies and intolerances (including coeliac disease) have been reviewed in the context of reducing the incidence of such diseases (22).

Allergens in cereals

Recently it has been suggested, based on the analysis of alpha amylase trypsin inhibitors (ATIs) genes, that ATIs (which are known as allergens in cereals) are low or even absent in ancient wheat (Einkorn) (19, 20) compared with modern bread wheats.

However, coeliac disease affects 1-3 percent of the population, whereas true wheat allergy is very rare, affecting only <0.2 percent of the population.

Accordingly, the question arises why so many individuals (>40 percent in the USA, >15 percent in Australia, increasing numbers in other regions) feel more comfortable on a gluten-free or wheat free diet?

Several popular nutritional plans, such as the Paleolithic diet (6-9) and diets more recently proposed by Davis, in “Wheat Belly” (10) and Perlmutter in “Grain Brain” (21), have suggested that wheat consumption has adverse health effects leading to numerous chronic diseases. Such suggestions are based on different hypotheses relating adverse health effects to wheat gluten, wheat lectins and wheat protein digestion-derived opioid-like peptides, including impacts on eating behavior.

With this, the authors of these books follow a recent trend to relate the cause of obesity to one specific type of food or food component, rather than to multi-factorial causes including food over-consumption and inactive lifestyle in general (11, 12).

Hundreds of proteins

The wheat grain contains many hundreds of individual proteins, which may have structural, metabolic, protective or storage functions (as reviewed by Shewry et al., (3)).

They include the gluten proteins, which are the major storage components and may account for up to 80 percent of the total grain protein (4). Higher intakes of whole grain products, which in the US and Europe are mainly based on wheat, are associated with reduced risks of Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, some types of cancer as well as a more favourable weight management (5).

For the general population whole grain consumption in general should be considered as healthy, helping to reduce chronic disease risk significantly (24).

As reviewed recently (13, 14) hard data about adverse human health effects of wheat components such as gluten and lectins (beyond coeliac disease and wheat allergy; 22), including aspects of weight management and insulin resistance are, however, not available and as well as there are currently no grounds to advise the general public to not consume this common dietary staple. This conclusion is further supported by the outcome of a recent cohort, where it was observed that individuals who consumed recommended amounts of (whole) wheat had the least amount of abdominal fat accumulation (15).

|

| Fig 2: Experimental red line |

For example, in one study in rats, excluding gluten from the diet showed a favourable impact on reducing fat tissue increase (16). The authors concluded that gluten exclusion may help to reduce body weight and can be a new dietary approach (in humans) to prevent the development of obesity and related sickness.

The latter is a conclusion which, lacking any supporting human data, seems rather premature.

Ancient versus modern wheat varieties

Another trial aimed to study the effect in humans of Khorasan wheat (Kamut, a putative ancient grain related to “ancient” tetraploid durum wheat), replacing “modern wheat in the diet”, on cardiovascular risk parameters (17).

Based on the obtained data it was concluded that a replacement diet with ancient wheat products could be effective in reducing disease risks.

The publication gave no information on the recipe of the products and the way they were processed before consumption, giving rise to many questions.

In a more recent study the same research group (18), studied the effects of consuming organic, semi-whole-grain products derived from Triticum turgidum- subsp. turanicum (ancient wheat), replacing a modern wheat based diet, on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) associated symptoms and inflammatory/biochemical responses.

The authors reported a significant improvement of gastrointestinal symptoms after the ancient wheat intervention period.

In addition, a significant reduction was observed in inflammation markers.

Also in this study no data were presented about the product recipes and the processing and final composition of the products. Although the authors stated that ancient wheat resulted in improvements, it cannot be excluded that compositional changes as a result of food processing may have played a role.

More or less simultaneously, it was suggested that a high content of so-called FODMaPs (fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides and polyols) plays a role in intestinal intolerance (23).

However, these carbohydrate compounds are not at all specific to bread wheat, and also occur in many other foods.

Roughly six percent of the general population seems to benefit from a gluten-free or wheat-free (or low-FODMaP) diet, although the degree of the benefit (as well as the severity of the original symptoms) is less well described.

Based on the findings listed above and the current social media drive to reduce the consumption of gluten-containing grains, it can be expected now that withdrawal of grains/cereals from the diet will result in an undesired replacement by less healthy, less nutrient and dense foods.

The cereal supply chain is being blamed to feed the world with sick making cereal products, much based on flawed interpretations of research data and/or statements of blogging activists. On the other hand NO SOLID comparative data are available on ancient vs. modern grains and the effects of their specific processing e.g. in bread making, let alone on the influence of consumption on gastrointestinal and general wellbeing.

Call for action

The entire cereal supply chain must respond to these developments.

We consider there is an urgency to perform double-blind ‘placebo’-controlled human intervention studies addressing the effects of different wheat types, their components and their processing steps towards end products to investigate the effects of consuming these completely analysed foods on human metabolism and health parameters.

Such human intervention trial addressing the effect of wheat-based foods, as consumed “as part of a typical daily human diet”, is the only way to obtain reliable data useful for future human dietary recommendations and appropriate food processing and product development.

To obtain reliable data the following research questions are proposed:

- What is the true composition of common bread wheat, spelt wheat and emmer wheat (proteins, carbohydrates, fibres)?

- What are the compositional changes that take place during food processing: controlled dough preparation (yeast “short” fermentation verses long fermentation using sourdough starter) and subsequent baking? Controlled extrusion and subsequent pasta or breakfast cereal making. Additionally, what is the final composition of the baked breads and produced pasta/breakfast cereals with regard to the components that potentially may lead to intestinal symptoms

- What are the in vivo effects (metabolic, functional – that is, breath, blood and stool analyses - and symptom occurrence) of the consumption of the obtained foods, (resulting from Step 2, including control) in a highly controlled cohort of IBS patients, in the context of gluten and FODMAP contents and composition?

- Do NOCEBO effects play a determining role in the perception of post-consumption effects?

To carry out the proposed project significant funding is required. In this respect we are requesting funds from four to six multinationals, with additional financial support of at least 15 other partners representing: farmers and millers, processing technology companies, food producers, NGO bodies.

Shared responsibilities

Interested ‘Gold Sponsors’ will be invited to build a strong core team and be active members of the steering team which will address the details of the program: design, methods, execution, communication, etc.

Additionally, they will be active members of the international communication working group.

Interested ‘Silver Sponsors’: Additional companies/organisations bringing in smaller funding contributions are invited to: 1) give written input on the program design, methods, execution, communication, etc; 2) will obtain regular news about progress, about gluten-free science and gluten-free market developments for the entire project period of three years.

References available on request.

Professor Shewry will be speaking at the Global Milling with GRAPAS Conference at Victam International in Köln, Germany on Thursday June 11. More HERE.

Read the magazine HERE.

The Global Miller

This blog is maintained by The Global Miller staff and is supported by the magazine GFMT

which is published by Perendale Publishers Limited.

For additional daily news from milling around the world: global-milling.com

No comments:

Post a Comment